In addition to the dotted symbols for each of the alphabet, one can indicate the French diacritical characters as well as punctuation. I will attempt to write in braille the short poem I wrote earlier using knotted fabric cords. Braille symbols can be integrated into works done in encaustic.

Braille slate and stylus

With the help of a small 4-line x 28 character plastic braille slate and stylus, it's possible to write in braille. Each dotted character is manually punched onto the paper using the 6-dot matrix; the words are scribed in reverse (from right to left) using the slate and stylus, producing the embossed dots that are visible when the paper is turned over.

In addition to the dotted symbols for each of the alphabet, one can indicate the French diacritical characters as well as punctuation. I will attempt to write in braille the short poem I wrote earlier using knotted fabric cords. Braille symbols can be integrated into works done in encaustic.

In addition to the dotted symbols for each of the alphabet, one can indicate the French diacritical characters as well as punctuation. I will attempt to write in braille the short poem I wrote earlier using knotted fabric cords. Braille symbols can be integrated into works done in encaustic.

International Morse Code

|

Basic IMC

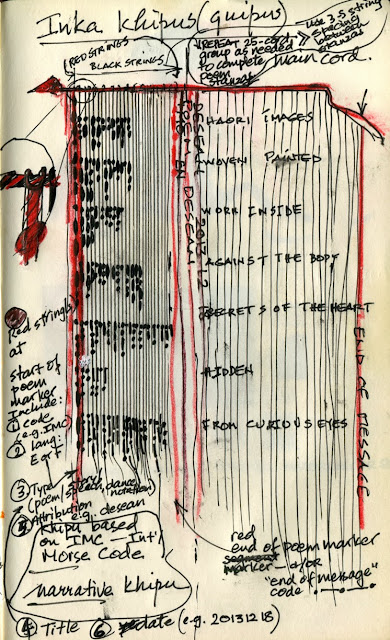

As illustrated in the knotted poem example in a previous post:

- A dot knot will consist of a single knot

- A dash knot will consist of five repeating knots

- Vertical spacing between a horizontal line of text will be equal to about 3-5 knots

- An unknotted vertical cord means a horizontal space between words

Knotted textile poetry

This drawing shows how my poems might be written and read, from left to right, with vertical knotted textile strings attached to a horizontal primary red cord with a fancy beginning knot.

The vertical red cords to the left would indicate basic information such as code used (IMC), language (French/English), title, attribution (author) and date. The knotting would use reflect the dots and dashes of the International Morse Code which allows for the use of French diacritical characters. The example on the right shows the decoded poem. The codes for start and end of message (poem) are also used.

The knots on the vertical red cords are read from top to bottom,whereas the knots on the black cords are red from left to right.

Inkan khipu

I've been doing research on ancient Inkan khipus from Peru. You may be wondering what a khipu is. They were a series of knotted textile strings that hanged vertically from a main cord and were intended as a record-keeping device. It was their way of keeping ongoing records on the number of crops and animals. Much research has been done on these based on the remaining khipus that have survived since 1400 AD. The data found in the khipu can now be read, based for example on the textile, colour and number of strands of the strings, the number and position of knots, etc.

The khipu shown above, part of the 109 Series, was found at the Laguna de los Condores, Peru by Dr. Gary Urton who has researched khipu extensively and maintains the Khipu Database Project at Harvard University.

My interest, however, lies mostly with the "narrative" khipu which were used, it seems, to recount stories and recite poems,rather than with the "accounting" type khipu. However, though there is some evidence in historic documents that such narrative khipu may have existed and the fact that there exists a small number of khipu that do not fit the "accounting" type, researchers have still not been able to decode them. Narrative Threads: Accounting and Recounting in Andean Khipu, edited by Jeffrey Quilter and Gary Urton, contains several chapters authored by a multidisciplinary group of researchers who met to discuss the possibility of "narrative" khipu.

The fact that there is a possibility that there existed an ancient tactile and textile-based system to record and recount stories and poems fascinated me. In the book mentioned above, Jeffrey Quilter, proposes in his paper, Yncap Cimin Quipococ's Knots, that the "narrative" khipu may have made use of a binary system similar to Morse code, to record their stories and poems. Urton also raises the strong possibility that such a binary system may have been used.

This revelation prompted me to adapt such a khipu-like system of recording my poetry using knotted strings and International Morse Code.

|

| Khipu UR010 (Photo: Dr. Gary Urton) |

My interest, however, lies mostly with the "narrative" khipu which were used, it seems, to recount stories and recite poems,rather than with the "accounting" type khipu. However, though there is some evidence in historic documents that such narrative khipu may have existed and the fact that there exists a small number of khipu that do not fit the "accounting" type, researchers have still not been able to decode them. Narrative Threads: Accounting and Recounting in Andean Khipu, edited by Jeffrey Quilter and Gary Urton, contains several chapters authored by a multidisciplinary group of researchers who met to discuss the possibility of "narrative" khipu.

This revelation prompted me to adapt such a khipu-like system of recording my poetry using knotted strings and International Morse Code.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)